|

Discovering and

Preserving Hoosier Heritage

Dr. James L. Cooper

Indiana’s

under-stated beauty of gently rolling hills, patch-work fields,

and timber stands broken by ambling creeks and modest rivers

nourishes a quiet, down-home, rural lifestyle long associated

with “Hoosiers.” For a century and a half, however, rural

Indiana has been increasingly complemented by urban development.

From the holler to the farmstead, to the small town, and to the

city center, a wealth of diverse spans has enriched Indiana’s

natural and man-made landscapes. Much remains wonderfully

available for discovery and exploration.

The bites and images on this site offer snapshots that arise

from considerable rummaging through records and wandering in a

pickup truck across Indiana for nearly three decades. You will

find a pronounced passion for the stories we have found – a

passion which reaches beyond Indiana’s historic bridges

understood as nostalgic Linus blankets or as easy avenues into

an imagined, simpler rural past. Instead, we will explore the varied and extensive inventiveness of our

designer and artisan forbears with the various materials

available when, in ages unlike our own, risk-taking and

efficient use of materials were practiced and honored.

explore the varied and extensive inventiveness of our

designer and artisan forbears with the various materials

available when, in ages unlike our own, risk-taking and

efficient use of materials were practiced and honored.

Today’s

covered bridge festivals and coffee-table picture books

undervalue the rich heritage of design and construction

represented by the timber spans which once graced our

roadways. Inventive elements are under the covers, if

the visitor is troubled enough to look inside. The

trusses speak to the great skill of the bridge-building

carpenters and blacksmiths once prominent in Indiana. In

the world of preservation, surviving Hoosier spans are

akin to the preserved houses of notable White Men. The

unroofed, low, and often unsided smaller timber trusses

and the trestle spans that provided the majority of the

bridges in any Indiana county before 1880 are now, like

worker housing, all gone.

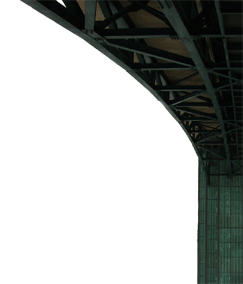

The

Iron Horse that knit together the increasingly industrial

workshops of the eastern United States following the Civil War

gradually changed Hoosier bridge trusses from timber to iron

and, from about 1890 onward, to steel. The earliest iron bridges

erected in Indiana were typically designed and fabricated in

Ohio, sent by rail to the train station closest to the erection

site, and then raised on foundations which local masons prepared

for the imported metal superstructure. Hoosier

designer-engineers soon invented some or their own truss formats

and iron workers developed a home-grown metal fabricating

industry which came to serve both Indiana and, in time, many

sites to the south and west. Buried in the under-maintained,

often-rusting metal bridges that may look like scrap heaps

sitting on the back 40 are stories of creative genius worth

uncovering and recounting.

| |

Friendship Bridge, Ripley County |

|

|

|

|

Falsework for supporting

arch and ginpole for lifting limestone block.

|

Stonework complete without

fill in 1909. |

1913 Postcard.

|

| |

|

--photos

courtesy of Ripley County Historical Society |

To

claim any considerable innovative design for the local

masons who laid up hundreds of stone arches, clams, and

clappers in the Indiana countryside or city would be to

undervalue invention as old as the Romans. But the

craftsmanship of many local Hoosier stone-cutters and

masons whose work is still exhibited in extant stone

structures on our highways is in league with that of the

Romans. Indiana stands second to none in the quarrying

and working of dimension Oolitic limestone used widely

to face monumental buildings across the United States.

The bridge-builders, however, rather largely relied on

the harder, blue, Laurel, or Niagara limestone quarried

mostly in the southeastern part of the state.

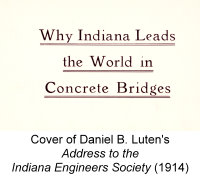

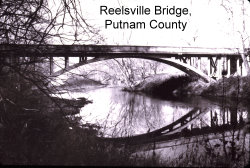

Concrete

bridges worked especially well in Twentieth Century cities

anxious to soften their gritty industrial image and to emphasize

civic

space. In the world of concrete bridge design and

construction Indiana has national significance. Its own Daniel

B. Luten held more patents on design and construction methods

early in the Twentieth Century than all other

Americans

combined. Luten-design could be found not only across Indiana,

but in tens of thousands of spans across the U.S.A., Canada, and

Mexico.

To honor the Hoosier spanned heritage discovered and explored,

we should strive to preserve as much of it as is possible and

practical. We are enriched by its beauty, rewarded with the

diverse community identities it bestows, and nurtured against

cultural amnesia through active connection with our roots.

Preservation means much more than keeping historic bridges in

the service for which they were designed as long as possible. It

also includes resistance to remodeling and transforming that

heritage into something else by replacement one bridge member at

a time. We need not live in a world of heritage mirage and

Disneyland make believe when in-kind repairs can retain the

original design and respect the original craftsmanship, often at

a fraction of the cost of replacing it.

|

|

|